Many people celebrate the Fourth of July as the birthday of the United States, but the actual events on that day involved only a half dozen people. On July 4, 1776, the Declaration of Independence was approved and signed by the officers of the Continental Congress in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. Most of the other members signed during a ceremony on August 2.

Is the Fourth of July the day the U.S. declared its independence? Explore all the dates during the summer of 1776 that are associated with the Declaration of Independence:

- July 2: Declaration of Independence Resolution adopted by the Continental Congress

- July 4: Declaration of Independence signed by the officers of the Continental Congress

- July 8: First public reading of the Declaration of Independence

- August 2: Declaration of Independence signed by 50 of the 56 men who signed the document

Explore texts that include the stories surrounding the Declaration of Independence. Possibilities include reference books, encyclopedias, and specific texts, examples of which appear in the Independence Day Book List. With your students, consider why there are so many different dates and why we celebrate the nation's birthday on July 4.

This page features the Declaration of Independence along with information about its writing and preservation, a timeline of its creation, and information on the signers.

As on online companion to the television series Liberty! The American Revolution, originally broadcast on PBS, this webpage focuses on the events of July 4, 1776. Be sure to explore the site for lesser-known facts. For instance, did you know that Congress designated a woman as the first official printer of the Declaration?

On July 8, 1776, the Liberty Bell was rung in Philadelphia to announce the first public reading of the Declaration of Independence. This National Park Service site includes facts about the Liberty Bell and its historic significance during the American Revolution.

Each year, the Hannibal Jaycees sponsor National Tom Sawyer Days during the Fourth of July weekend to celebrate the town's most well-known citizen, Mark Twain. The highlight of the event is the fence-painting contest, which begins on July 4 with local competition and advances to state and national contests over the next three days.

Mark Twain uses great detail to capture the locations of his tales. Readers feel as if they have actually traveled with Twain to the settings of his stories and novels. Choose a particular scene in one of Twain's works and do a close examination of the setting. First, have students map the story setting, using the interactive Story Map. Then discuss the setting using these prompts:

- How does Twain use extended description, background information, and specific detail to make the setting come alive for readers?

- How do the main characters fit into the setting-do they seem at home or out of place?

- How do their reactions and interactions with the setting affect the realism of the location?

Discuss the techniques that Twain uses to make the settings in his stories vivid and real to the readers and the extent to which these techniques are effective.

Visit this PBS site to learn about Twain through his writing and view his scrapbook.

Visit Hannibal, Missouri, where Sam Clemens and other children who influenced characters in Tom Sawyer grew up.

Visit this archive, produced by the Electronic Text Center at the University of Virginia, to find pictures, transcriptions, and analysis of Twain's writing, and information about the marketing of his books.

On the morning of July 1, 1874, the first zoo in the United States, the Philadelphia Zoo, opened its doors to visitors who, for a quarter or less, could visit and view the 813 animals that lived there. Today, the Philadelphia Zoo has more than twice as many animals and four times as many visitors as it had during its first year of operation.

Much more has changed in the zoo than the number of animals and visitors. Visit the Philadelphia Zoo's History Overview to learn more about the first zoo in the United States. Then have your class compare features and aspects of the first zoo with a modern zoo, using the interactive Venn Diagram tool. Ask your students to think in particular about the differences in how animals are cared for and the habitats where they live.

Once your students have considered how zoos have changed over the past century, invite them to imagine the zoo of the future. How will animals be cared for? What will the zoo look like? Who will visit the zoo? What will be the primary mission of the zoo? In small groups, students can explore these questions and then design their own zoo of the future using drawings, posters, dioramas, or a similar display technique.

National Geographic Education’s encyclopedia entry on zoos includes information on zoo history, types of zoos, zoo specialization, and conservation efforts. Related terms are defined in a Vocabulary tab. The website includes related reading suggestions, illustrations, and links to related National Geographic Education resources.

This site highlights the traveling Robot Zoo exhibit. This online exhibit explains how the robots work and how they relate to the real animals that they are modeled after. Students can even pet the animals online!

If you don't have a zoo nearby, you can use this site to find pictures and information about animals and their habitats. This site also features Classroom Resources, such as free curriculum guides and information about outreach programs.

Nine contestants participated in the first National Spelling Bee, sponsored by the Louisville, Kentucky, Courier-Journal in 1925. Now, over 250 student champions, ranging from 9- to 15-years-old, travel to Washington, D.C., to compete in the National Spelling Bee. The competition takes place during May each year. The National Champion receives $28,000 in cash and savings bonds as well as reference resources for his or her home library.

The National Spelling Bee competition has been broadcast nationally on ESPN and during primetime on ABC. In his article "All I Need to Know about Teaching I Learned from TV and Movies," Kenneth Lindbloom compares the competition to shows like Jeopardy. Lindbloom explains, "One might speculate that these events garner interest because they are contests with one winner and many losers. But more difficult contests-Westinghouse science winners, for example, or creative-writing contest winners-don't get the kind of publicity memorizers of trivia get." Ask your students to consider this with the following questions:

- Why do some contests get more publicity than others? What makes the National Spelling Bee interesting to the general public?

- Is the National Spelling Bee a sports event? Why has it been broadcast on ESPN?

- What counts as knowledge on television? What knowledge is seen, and what kinds of knowledge are not seen?

The official homepage for the competition includes details on the student spellers, their sponsors, the rules for the competition, and statistics. During the competition, photos of the events will be added to the site.

By Margaret Y. Phinney, this page from the Natural Child website explains invented spelling and emergent writing and includes suggestions designed to encourage children's writing and use of invented spellings.

This Scholastic website features essays that contain strategies aimed at integrating spelling into the reading and writing curriculum and helping students to improve their spelling skills.

ReadWriteThink's Word Wizard interactive allows students to spell words based on four favorite children's books. Students can read and listen to clues and click the hint button if they're stuck.

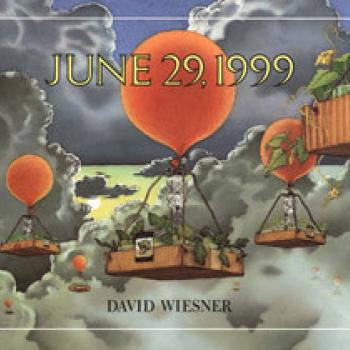

In June 29, 1999, main character Holly Evans undertakes a scientific project that appears to have gigantic results when huge vegetables begin landing on the planet. Yet she's still not sure where the vegetables all came from.

David Wiesner, author of June 29, 1999 (Houghton Mifflin, 1992) and two-time Caldecott Award winner, composes humorous books with delightful illustrations that surprise the reader. In fact, in June 29, 1999, Wiesner's illustrations are indicative of the emotions of the various story characters: people are delighted, surprised, and, in some cases, curious. Such illustrations provide an excellent opportunity for discussion of feelings and how they are expressed wordlessly through the talent of the illustrator. Explore the pictures in Wiesner's book carefully and identify elements that make the emotions in the story obvious to someone reading the book. Your students might then create lists of words and their own illustrations to express the feelings portrayed.

If you're looking for information on Wiesner's books, his biography, and related resources, this Houghton Mifflin site is for you. It even includes illustrations and notes on Wiesner's creative process.

Focusing on Wiesner's Caldecott Medal–winning book, this series of classroom activities includes comparing Wiesner's book to other versions of the three pigs story as well as links to a Kidspiration story map and additional resources.

This site provides recommended wordless picture books for children.

When she was born in Alabama on this day in 1880, Helen Keller was a normal baby; but when she was nineteen months old, she lost both her hearing and sight after an illness. As an adult, Keller was a writer, an educator, and a social activist.

In 1887, Keller learned to talk using a finger alphabet after her well-known breakthrough with Annie Sullivan at the family's well pump. The finger alphabet that Keller learned to communicate with Sullivan, her family, and eventually, many others was a basic version of the system that is now known as American Sign Language. Have your students explore the American Sign Language browser from Michigan State University and try using a few signs. Discuss how ASL differs from spoken English and how the two are similar. During the discussion, introduce the misconceptions about ASL addressed in the article Common Myths about Sign Language.

Ivy Green, Helen Keller's birthplace, sponsors this website on Keller's life and accomplishments as well as pictures and details on the birthplace, its grounds, and events that take place at Ivy Green.

The focus of this blog will be to synthesize research regarding the use of technology in the literacy development of deaf and hard of hearing students.

The Helen Keller Archival Collection at the American Foundation for the Blind (AFB) is the world’s largest repository of letters, speeches, press clippings, scrapbooks, photographs, architectural drawings, artifacts and audio-video materials relating to Helen Keller.

Eric Carle, born in Syracuse, New York, in 1929, has illustrated more than 60 books. One of his most beloved books, The Very Hungry Caterpillar, has been translated into more than 25 languages and has sold more than 12 million copies.

Eric Carle's illustrations feature paper collages, so after reading some of Carle's books you might create your own torn paper collages. Or if you're ready for more of a challenge, try creating Word Collages. Have students choose a scene, an emotion, an animal, or a person. Then students search out or create words, phrases, and sentences that illustrate what they've chosen. Words can be cut out of newspapers or magazines, created on a computer using a drawing program or the art tool in a word processing program, or drawn with markers or crayons. Assembled on a sheet of paper using glue or tape, the words should remind the reader of the scene, emotion, animal, or person that the student has chosen.

Eric Carle's own website includes information on all of Carle's books, upcoming events, forthcoming publications, and the Eric Carle Museum of Picture Book Art.

Devoted to national and international picture book art, this museum emphasizes ways of combining visual and virtual literacy. The virtual tour provides great visuals, which could be a springboard for language or visual arts projects.

Scholastic's Eric Carle Author Study includes information from an interview with Carle, background information, a bibliography, and a variety of classroom activities using several Carle books for art, science, math, social studies, and writing connections.

The National Gallery of Art offers this interactive tool for creating collages. Letters, numbers, signs, and shapes comprise the images available for use in the collage.

If someone placed an original 1868 typewriter in front of you, you might not be able to figure out what it was. With keys that look more like they belong on a piano keyboard, the original typewriters looked very little like even the manual typewriters you're likely to happen upon today.

The invention of the typewriter led to the keyboards on the computers of today. Show your class a computer and a typewriter or two if you can find significantly different typewriters, such as a manual one and an electric one. Begin an inquiry-based study that compares typewriters to computers. Students can talk about everything from the appearance of the two tools to the way that one gets the final, finished product (a piece of paper with alphanumeric figures on it) to the different ways that they might use the two machines if they were composing a paper. As a conclusion to the project, ask students to hypothesize about how the shift from typewriters to computers changes the way that work is done.

Note: If you do not have access to typewriters and computers for the class to explore first-hand, pictures of the objects could be a reasonable substitute.

This site includes games, puzzles, links, contest information, and a calendar of trivia related to patents and trademarks. Divided into materials for grades K–6 and 7–12, the site also features information for parents and coaches.

Many inventions come about as a result of people playing with the things in the environment around them. Explore the pages of this Smithsonian National Museum of American History site to see play turn into invention-and then perhaps you can invent something as you play in the classroom.

This Smithsonian Institution resource explores the similarities between the office of today and the past. Related lesson plans, a timeline, and information about office equipment-including the typewriter-are included.

This site focuses on the history and evolution of typewriters.

Juneteenth is a celebration of the day in 1865 that word of Lincoln's signing of the Emancipation Proclamation, freeing all slaves, made its way to the state of Texas. The celebration name is a combination of "June" and "Nineteenth"—the day that the celebration takes place.

Juneteenth has grown into a heritage-centered event that focuses on family, community, education, and achievement—but its origins are still very important. How does the historical background of the day, as a celebration of freedom for the slaves of Texas, compare to other important celebrations of freedom in the United States?

Invite your students to compare Juneteenth celebrations to Fourth of July celebrations, using the Venn Diagram. What events take place on the two days? What do people do? How are the events described in the media? When students notice differences between the celebrations, ask them to hypothesize about the reasons. Conclude the discussion by asking students what conclusions they can draw about the ways that people celebrate and define freedom in the U.S.

Want to see what the original Emancipation Proclamation looked like? Visit the National Archives and Records Administration site, which includes historical background and photographs of the document.

This site explores the origins and history of the holiday, along with how to celebrate it in the workplace, community, and home.

This Library of Congress "America's Story" site explains the background and local celebrations of the emancipation in Texas.

Here is a list of books to introduce the holiday's stories and traditions to the youngest readers.

President Woodrow Wilson signed the law that proclaimed June 14 each year to be celebrated as the national holiday of Flag Day. Every year since 1916, this day has been a day of patriotic celebration.

Share with your students the songs from Patriotic Melodies from the Performing Arts Encyclopedia of the Library of Congress. Ask your students to consider how America, Americans, and the flag are represented in the various songs and to hypothesize about the reasons for the differences that they notice. With 27 songs to choose from, each student can work on a separate song or small groups can tackle several songs. The songs range from well-known tunes such as "When Johnny Came Marching Home" and "You're a Grand Old Flag" to more obscure songs like the "Library of Congress March."

This Library of Congress site includes historical background, photos, and artwork that explain how the flag and Flag Day came into being. Have students write their own stories about their personal interaction with the flag, or have them interview members of their family or community and write their stories.

The American Flag Foundation encourages all Americans to "pause for the pledge" at 7:00 p.m. on Flag Day. This site includes information on the program and a collection of educational resources including flag Q&A, flag etiquette and retiring, and information on the Pledge.

This site provides historical information about the U.S. flag, as well as images of each of the official versions of the flag throughout America's history. The site also features a variety of patriotic writings, including poems, essays, letters, and songs.

From the Verizon Literacy Network, this interactive activity includes 25 hidden flags for users to find, along with an interesting fact about the flag at each location.